In times past, when a sitting member of Congress passed away time was taken from the other business of the House and/or Senate for members to make remarks, for the record, on the life and works of their late compatriot.

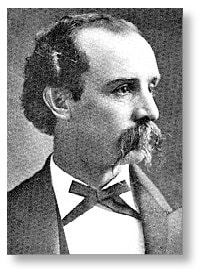

These comments and addresses were then gathered and published in book form, and made available to the public. It is still possible to find these volumes from time to time on the shelves of old & rare book dealers, and such was the case with "Memorial Addresses on the Life & Character of George Washington Gordon". When this 1913~vintage book was redeemed from a dark corner of the shop of a local bookman, it was found to contain an un~dated and un~attributed clipping, most likely saved from a Nashville newspaper. The text of that clipping is reproduced below.

The Last of the Line

General George W. Gordon, the last Confederate General, has passed from the halls of the United States Congress. There never be another. The first one came when the disability of those who had served the Confederacy was removed. They have been in every Congress since for nearly half a century. There is none left, unless, perhaps, it may Basil Duke, with sufficient physical strength to perform the duties of a Congressman, and it is not likely that he or any of the other few have that inclination.

Gordon, the last of the illustrious list, was one of the most typical of the men who served, who made, the South. A gentle, courteous man, he was without pretense. The forty odd years since the war had not changed him much. Many Nashville people had the opportunity of seeing him less than a year ago at the State reunion of Confederate Veterans at Franklin. They saw an old man then in the beginning of the decline which ended in his death, but not differing essentially from the youth of the early sixties. He preserved in his manner and his habits of thought much that was characteristic of the elder day.

Gordon, like many of the Generals of the gray, was not a West Point man. He was educated in this city, at the University of Nashville, which was operated at that period in a sort of merger with the Western Military Institute, much as it has been for the past thirty~five years with Peabody College. When the call for volunteers came, its entire student body marched away under the stars and bars. Among them was that Sam Davis who was shortly to take his place with the heroes of the ages. Gordon was graduated two years earlier. Whether or not he and Davis were fellow students can probably never be determined now, for the records of the institution were in large measure destroyed when the Federals took possession of the buildings.

What Gordon did during the four years of fighting is so much like what all other Confederate soldiers did that it seems hardly more than a repetition. He began as a regimental drill master and was promoted to Brigadier General. He was three times captured and as many times wounded. He was in every important battle participated in by the Tennessee troops. No man saw harder service, nor faced it more gallantly.

But the stricken field and the beleaguered city, the camp, the march, privation, imprisonment, wounds, were not the worst. The Confederate soldier's hardest fight came after peace was declared, when a more serious condition than war existed, when the camp followers of the victors were fattening on the blood of the vanquished.

It was a time when a revolution was fought and won in the darkness of night, mystery surrounding it, in defiance of that which purported to be the administration of law. Certain men thought it necessary, in order to preserve white civilization in its purity, that there be formed an organization for dispensing justice, for taking the law and its administration out of the hands of the constituted authority. They called it the Ku Klux Klan. General Nathan Bedford Forrest became its supreme commander. General George W. Gordon wrote its ritual. Both were largely instrumental in its formation and in its conduct. The order for its dissolution, when it was believed that its work was done, came from General Forrest. Gordon and Forrest and the others thought they were leading a movement for the protection of society, for the ultimate supremacy of law. Beyond the borders of their section the movement was regarded as flagrant lawlessness. But one fact seems certain ~ that the Ku Klux Klan is probably the only lawless organization known to history that voluntarily disbanded because its leaders believed that order was in a degree restored.

That those who led the movement were law~abiding citizens after its dissolution is nowhere denied. Gordon was typical of them. He practiced law quietly for many years; was for a time in the service of the Interior Department of the United States Government; for a time superintended the educational system of his city and was called to represent his district in Congress. As the last Confederate General to sit in that body, he maintained the high standard of service of the many who had gone that way before him. And the Congress and the nation owe much to him and his comrades.

These comments and addresses were then gathered and published in book form, and made available to the public. It is still possible to find these volumes from time to time on the shelves of old & rare book dealers, and such was the case with "Memorial Addresses on the Life & Character of George Washington Gordon". When this 1913~vintage book was redeemed from a dark corner of the shop of a local bookman, it was found to contain an un~dated and un~attributed clipping, most likely saved from a Nashville newspaper. The text of that clipping is reproduced below.

The Last of the Line

General George W. Gordon, the last Confederate General, has passed from the halls of the United States Congress. There never be another. The first one came when the disability of those who had served the Confederacy was removed. They have been in every Congress since for nearly half a century. There is none left, unless, perhaps, it may Basil Duke, with sufficient physical strength to perform the duties of a Congressman, and it is not likely that he or any of the other few have that inclination.

Gordon, the last of the illustrious list, was one of the most typical of the men who served, who made, the South. A gentle, courteous man, he was without pretense. The forty odd years since the war had not changed him much. Many Nashville people had the opportunity of seeing him less than a year ago at the State reunion of Confederate Veterans at Franklin. They saw an old man then in the beginning of the decline which ended in his death, but not differing essentially from the youth of the early sixties. He preserved in his manner and his habits of thought much that was characteristic of the elder day.

Gordon, like many of the Generals of the gray, was not a West Point man. He was educated in this city, at the University of Nashville, which was operated at that period in a sort of merger with the Western Military Institute, much as it has been for the past thirty~five years with Peabody College. When the call for volunteers came, its entire student body marched away under the stars and bars. Among them was that Sam Davis who was shortly to take his place with the heroes of the ages. Gordon was graduated two years earlier. Whether or not he and Davis were fellow students can probably never be determined now, for the records of the institution were in large measure destroyed when the Federals took possession of the buildings.

What Gordon did during the four years of fighting is so much like what all other Confederate soldiers did that it seems hardly more than a repetition. He began as a regimental drill master and was promoted to Brigadier General. He was three times captured and as many times wounded. He was in every important battle participated in by the Tennessee troops. No man saw harder service, nor faced it more gallantly.

But the stricken field and the beleaguered city, the camp, the march, privation, imprisonment, wounds, were not the worst. The Confederate soldier's hardest fight came after peace was declared, when a more serious condition than war existed, when the camp followers of the victors were fattening on the blood of the vanquished.

It was a time when a revolution was fought and won in the darkness of night, mystery surrounding it, in defiance of that which purported to be the administration of law. Certain men thought it necessary, in order to preserve white civilization in its purity, that there be formed an organization for dispensing justice, for taking the law and its administration out of the hands of the constituted authority. They called it the Ku Klux Klan. General Nathan Bedford Forrest became its supreme commander. General George W. Gordon wrote its ritual. Both were largely instrumental in its formation and in its conduct. The order for its dissolution, when it was believed that its work was done, came from General Forrest. Gordon and Forrest and the others thought they were leading a movement for the protection of society, for the ultimate supremacy of law. Beyond the borders of their section the movement was regarded as flagrant lawlessness. But one fact seems certain ~ that the Ku Klux Klan is probably the only lawless organization known to history that voluntarily disbanded because its leaders believed that order was in a degree restored.

That those who led the movement were law~abiding citizens after its dissolution is nowhere denied. Gordon was typical of them. He practiced law quietly for many years; was for a time in the service of the Interior Department of the United States Government; for a time superintended the educational system of his city and was called to represent his district in Congress. As the last Confederate General to sit in that body, he maintained the high standard of service of the many who had gone that way before him. And the Congress and the nation owe much to him and his comrades.